«Window on the courtyard, window on society

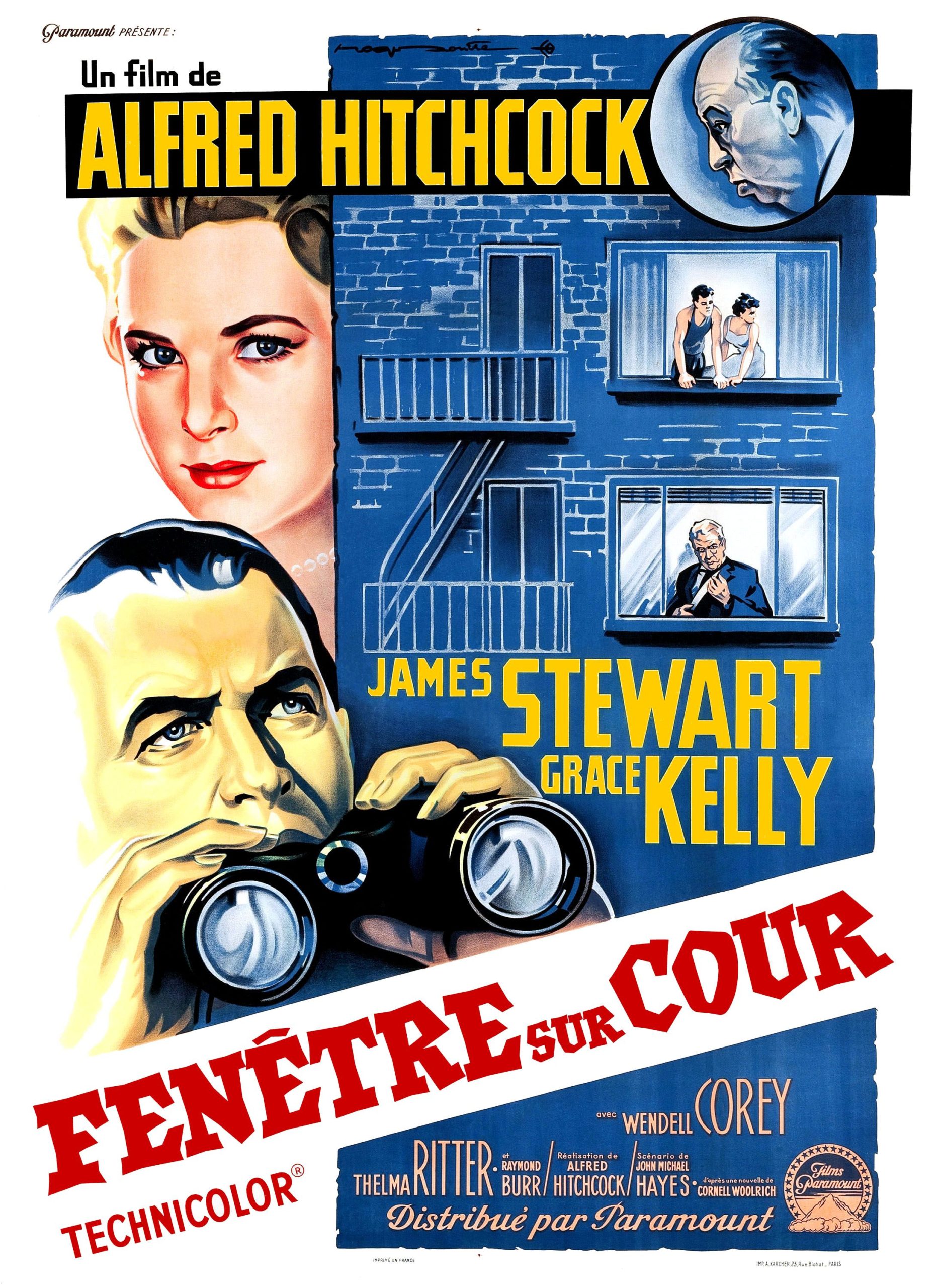

Archives du Septième Art

Jeff Jefferies (James Stewart) is confined. No virus in the air, but a broken leg. This photojournalist isn't used to staying at home. Here, he has no choice. So he gets bored. He spends his days looking out of the window of his apartment, which overlooks a courtyard. Every day, he spies on everything his neighbors are doing. There are pleasant sights, such as the one he unwittingly sees Miss Torso, the young and ravishing dancer, when she stretches her legs sensually in the air, or when she dresses up with the rest of her body in the air. Funny shows, like the household scenes of an old couple, or the early weariness of a young couple. A very sad show, that of Miss Cœur Solitaire, who dreams of a love that never comes, but simulates the reception of an imaginary lover serving her a drink that will never be drunk.

And then there's the film's central spectacle: another couple. Mrs. Thorwald has the flu in bed. Mr. Thorwald goes back and forth all day. Jeff, struggling to sleep, notices that Mr. Thorwald's comings and goings continue at night. Strange. He discreetly observes the situation with his photographer's telephoto lens. In addition to his comings and goings, Mr Thorwald sometimes carries a trunk, sometimes a saw, sometimes a rope, sometimes a knife. He looks anxious and tense. And Mrs Thorwald, although bedridden, has disappeared. Jeff wants to know more. Too many suspicious elements. What if it was a domestic murder? Jeff's nurse, who visits him on a daily basis, also takes an interest in the case. So does his girlfriend, Lisa (played by sublimissimissimissime Grace Kelly!) who, annoyed at her companion's lack of attention to her, also turns her gaze to the court. Oh, boy! The three budding detectives are convinced. It's got to be murder!

In-field and out-of-field

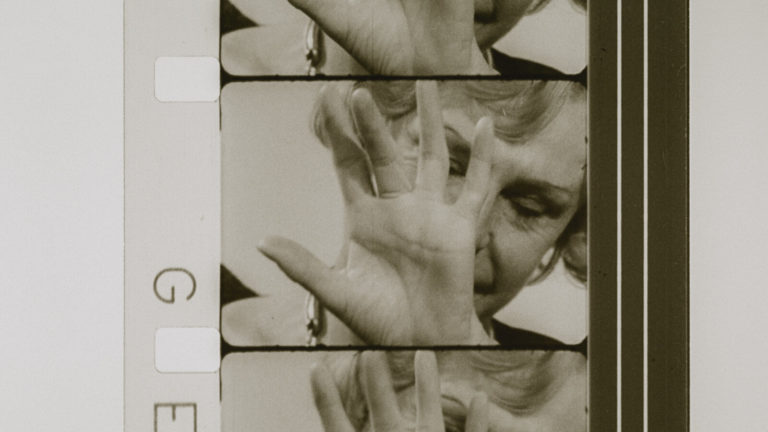

Courtyard window may not be Hitchcock's best film, but it's unquestionably his greatest stroke of genius. At least from a technical point of view. Jeff is behind closed doors. He can watch, be moved, gawk, worry, but he can't intervene. Just like the spectator. The viewer observes the action on screen from the comfort of his armchair, but has no way of intervening in the film. In fact, the viewer's gaze is Jeff's own. From his window, he sees everything, without seeing everything. All that's available in his field of vision is what's happening in his neighbors' windows. He does, however, have a good overview, since it's summer, it's very hot, windows are open and people are practically living in their windows.

This overall view is the view of the spectator, who sees everything that's being filmed as a whole. field, In other words, within the shots filmed by the camera. As the walls of the apartments are not just windows, there are intermediaries, from one room to another, that Jeff and the viewer cannot see. This is the off-screen. The film's entire plot is based on this. Jeff, without being seen, has seen enough, even more than enough, but he hasn't seen everything. He didn't see the presumed murder, nor the blood, nor the corpse, but he saw everything else. Like the viewer, whose thoughts, assumptions and concerns run parallel to those of the main character.

Split screen

The construction of the field, For most of the film, what we see is done in split screen. The only moments when this scenography does not intervene are the shots inside Jeff's apartment. The moments when he tries to be present to himself or intimate with his partner. But Jeff is obsessed with the outside, especially as there may, indeed certainly is, a murder at stake. And, of course, there's always something more interesting to observe on the outside: whether it's the dancer, the pianist, the couples, a highly original sculpture, a little dog with a bad ending.

Whereas at the beginning, it's the spectator who joins Jeff's gaze, it's Jeff who, as the film progresses, adopts that of a spectator condemned to forget himself for the duration of a film session, to see only what the shots want to show him. The plans are drawn up by the director, i.e. Hitchcock, who appears in a cameo for a brief moment in an apartment, adjusting the hands of a clock. He is the master of time. He takes charge of us for the duration of a film he himself has determined.

Hell, heaven and beyond

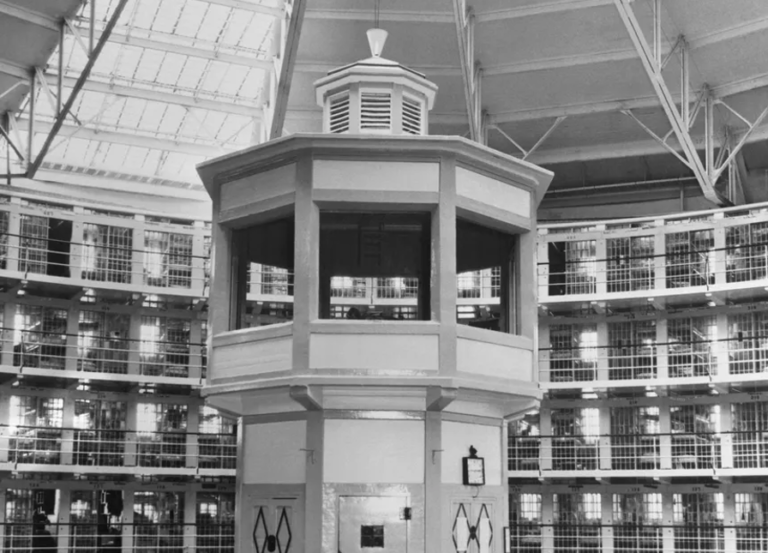

Visit split screen also implies that the separations between the windows separate the rooms, the apartments and those who live in them. Within the screen as a whole, that is, the view from Jeff's window, there are a multitude of scenes from the daily lives of different people. The screen as a whole is society; the windows are portraits. Courtyard window becomes totally social. It presents portraits of modern life in the 1950s. Without denouncing or praising anything, these portraits lead to the film's philosophical dimension, questioning Jeff and the viewer about marriage and its consequences, about life as a couple, about solitude, about individualism, about artistic creation in this solitude or, more generally, about everyone's relationship with otherness.

«Hell is other people,» says Sartre in Huis Clos precisely. Hell or not, these others are a necessity. Jeff embodies this in his dependence on the nurse who comes to take care of him every day. In his attachment to Lisa, whom he can't commit to proposing to, but can't let go. In his obsession with looking out the window. While he could ignore the alleged murder, he feels responsible for investigating it. On the one hand, it's voyeurism; on the other, it's responsibility to one's fellow man. Hell is other people. Heaven is other people too. Because happy or unhappy, we can't do without looking at others. What changes is the malevolence or benevolence of the gaze. Jeff oscillates between the two. Like the viewer. We are beings in split screen. We can't help it.

You have just read an article from our special operation «All about Hitchcock».

Leave a comment