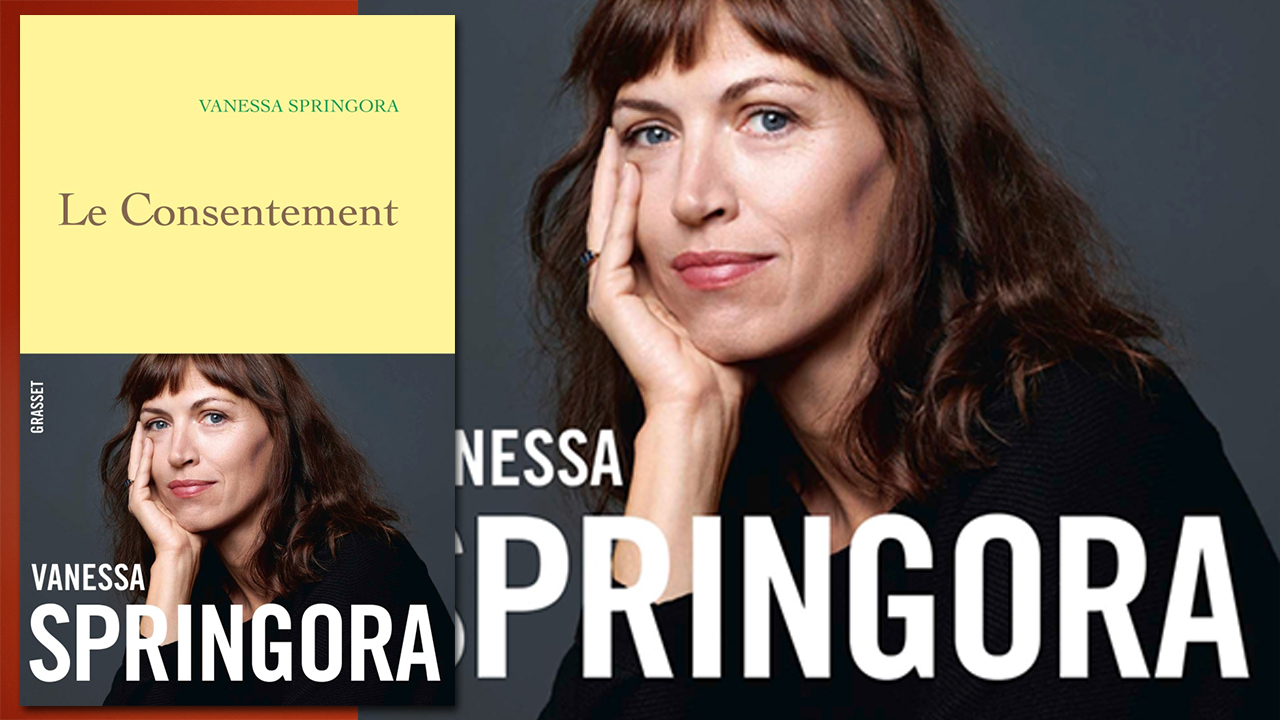

«Consent»: writing is undoubtedly a universal remedy

Vanessa Springora's narrative, which serves here as a remedy, exposes her distressing adolescence, shattered by the writer-ogre Gabriel Matzneff. She depicts the mechanisms of his domination and his militant paedophilia, which did little to alarm the literary milieu of the time, or her next-door neighbor.

Consent, which is the talk of the town and the media's bread and butter, has already sold over 85,000 copies. Unavailable today in bookshops in French-speaking Switzerland, as it is being reprinted, it is the story of V.’s (Vanessa Springora) distressing adolescence under the influence of the militant pedophile G. (Gabriel Matzneff). Put another way, it's the poignant tale of the fatal relationship between a 50-something writer-ogre, perfumed, seductive and subtle-minded, and a young teenager, not even 15, ingenuous, lost, quite alone and looking for love. The story, divided into six parts (L'enfant, La proie, L'emprise, La déprise, L'empreinte, Ecrire), is intended to be cathartic for V. It is a remedy, a means of revenge, too:

«For so many years, I've been circling in my cage, my dreams filled with murder and revenge. Until the day when the solution finally presents itself, there before my eyes, as if it were obvious: catch the hunter in his own trap, lock him up in a book.»

Brushing aside the dust of her childhood past, V. justifies how her meeting with G. later led to a relationship. She sets the scene in an unbridled, artistic environment, talks about her parents« marital quarrels, divorce, father's absence and so on. She shares her discoveries about adult sexuality and her own childhood sexuality, with its erotic games of gentle touching. The absence of a father figure fueled her need to find a father figure: »Since my father disappeared off the radar, I've been desperately seeking the gaze of men. Thus, a taste for reading, the search for a father and a certain sexual precociousness coupled with a need for attention laid the foundations for her future relationship with the writer-ogre.

We meet G. at a literary dinner. The young teenager V. feels drawn to this writer-ogre with his «cosmic presence». The mouse trap snaps and closes on her. Seduced, in love and blinded, G. becomes a close and intimate friend, picking her up from school as if nothing had happened, taking her for walks and holding her hand in the street, talking to her about art, introducing her to «the unparalleled heights of orgasm» in his Parisian maid's room. The relationship is consummated by V.'s total blindness, manipulated by G., an extraordinary predator, with whom she is infatuated and for whom she swoons with admiration. For the height of attachment is blindness itself:

«I'm in love, feel loved, like never before. And that's enough to erase all asperity, to suspend all judgment on our relationship.»

What's so distressing about this relationship is the indifference of the characters around them, who do nothing, who show no alarm, who let their relationship grow to the point of indulgence. The mother, shocked at first, but eventually accommodating, will even invite G. to eat at home several times, all three of them around the table:

«Sometimes she invites him to dinner in our little attic apartment. At the table, the three of us, around a leg of lamb with green beans, it's almost like a nice little family, Dad and Mom together at last, with me in the middle, radiant, the holy trinity, together again.»

And there will be many of these indifferent characters who don't do much. There's the Minors' Brigade, which investigating the writer-ogre. There are also complacent characters, from the gynecologist to Emil Cioran himself, not to mention the other who don't give a damn because, supposedly, that's just the way the times were and that, under the cloak of art, in the circles of writers, you can that other circles cannot. In the 70s and 80s, the image of freedom? To justify this complacency complacency of the time, an open letter in favor of the decriminalization of sexual relations between minors and adults, published in 1977 in Le Monde entitled «A propos d'un procès», signed by several left-wing intellectuals, including Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, André Glucksmann, Louis Aragon...

But fortunately, other characters try to guide V. in her choices, such as Denis, Youri, or classmates who, by whispering in her ear: «I saw your old man on a bus, kissing another girl», instill in her a saving jealousy. Again, it's dramatic that it's jealousy that leads V. to become aware of her abuse. But that's how the story goes. The young teenager's emancipation will be thorny and painful, and madness follows close behind, with its psychotic episodes. The sections La déprise, L'empreinte and Ecrire show V.«s journey towards her difficult reconstruction: »It took me a long time to let myself go with a man, without the help of alcohol or psychotropic drugs."

The reader will find it easy to writing style is simple, precise and fluid. Perhaps not aerial or poetic enough for some, vertigo is far away, but the author's need but the author's need to stick to the reality of the subject outweighs the form. Out of empathy the reader feels what V. feels. He questions himself, and the question raised raised by this story is the tolerance accorded to the so-called «privileged artist privileges before whom our judgment (...) must yield.»

Or how, because he was a talented artist, G. had managed to seduce the literary world of the time, notably with the publication of his diary. A diary is not exactly fiction. Indeed, how could his diary have been published, when it included «first names, places, dates and all the details which, at least for their close circle, would enable his victims to be identified, without ever prefacing these works with a minimum of distance from their content»?

V.«s pithy phrase sums up the problem: »Does literature excuse everything? It's up to the reader to answer these questions, which run through today's social mindset, according to his or her mood of the day. For the only reality of the book is the reader.[1]. And it's fair to say that the only real, unadulterated thought that comes to mind as we close this book is that writing, writing desperately, is without doubt a universal remedy.

[1] «The reality of the book is the reader.» A dog on the road, Pavel Vilikovský

Write to the author: arthur.billerey@leregardlibre.com

Vanessa Springora

Consent

2019

Editions Grasset

216 pages

Laisser un commentaire