Saturday's Netflix & chill - Loris S. Musumeci

Roma by Alfonso Cuarón is one of the reasons why our «Saturday's Netflix & chill» was released almost three months ago. How can you miss such a work simply because it's not being released via the classic theatrical channel? Even if the film is no longer in the most recent cinema release news, we have to talk about it. We have to talk about it. Since late 2018, it's been elevating Netflix. With The Irishman by Martin Scorsese, it provides the platform with a cinema space, a cinema lesson, a little gem that can be passed from tablet to smartphone for the general public.

A Mexican story, a universal story. In Mexico City's Colonia Roma district, domestic servants Cleo and Adela work for a wealthy, exemplary family. The father is a renowned doctor, the mother, Sofia, a fine, cultured chemist. The grandmother, stern and endearing. The dog, silly and affectionate. The four children are cradled by games and joie de vivre. And by the love of Cleo, who loves them like a mother. The father pretexts an important trip to Canada for his work, and flees the family to live out his love affair with a new conquest.

The women find themselves alone with their children. Life goes on. School, vacations, Christmas, New Year. Cleo is seeing a young man on vacation. She lets herself be taken, touched; she knows the boy intimately. In his body. Impregnated by a Sunday affair, she tells the father-to-be three months later. Seemingly delighted, he flees. Cleo is alone with her pregnancy. Sofia, just as alone. But two women alone create a whole. In solidarity with the abandonment they have each endured, they support each other through the toughest trials that 1971 has in store.

A divided reception

Roma clicks before you watch it. It clicks from the very first scene. The joy of entering a perfect cinematic landscape, pure, aesthetic, rich in references and symbols. Universal in its plot, which looks at the life of a little maid. But it's also worrying. Of witnessing a deception. Of being disappointed by a film that's too calculated, too polished, too perfect, too much of a masterpiece. A film that would be too unanimous, that we wouldn't have the right not to adore. When I clicked on play, I was still both delighted and worried. I came out of the film neither delighted nor worried. I came out fascinated, moved, with a full head and a light heart.

I think that's the case for many who have come to appreciate the film with the measure it deserves. Some cried masterpiece too soon, because it's Cuarón, because it's in black and white, because it's an auteur film, a social film, a philosophical film. Perhaps they failed to consider the film's hidden treasures, obsessed by the fact that, in any case Roma must be excellent. Perhaps they simply had a good feeling; they were delighted and were not disappointed. They rejoiced when the director was awarded the Golden Lion. Others dismissed the film's script and images, criticizing it as boring, heavy-handed and pretentious. They have every right to do so. To claim unanimous support for Roma, would be a betrayal of this strong, imposing work, which nonetheless leaves the viewer enormous freedom.

Cuarón pays tribute to Fellini

A freedom that draws on the references and memories of each individual. Roma weaves links and allows us to weave our own links to the resurgence of the past, to childhood, its places and senses, to films that have left their mark. Alfonso Cuarón allows himself this freedom. Just as the individual figure of Cleo is universal in scope, so Cuarón's particular feelings are universal. His homage to the great Italian director Federico Fellini taps into the depths of his own cinephilia, just as it does mine. But in a different way. He has his Fellini, I have mine.

Fellini, then, from whom the very title of the film is borrowed. Roma (2018) revisits a filmmaker's memories of Mexico in the early 1970s, Roma (1972) revisits a filmmaker's memories of Italy from the thirties to the sixties. Roma (2018) revisits Cuarón's childhood, adolescence, sorrows and happiness; Eight and a half (1963) and Amarcord (1973), two other Fellini films, revisit the fantasies, dreams, feelings and career of the man who became one of the major figures in cinema, art and culture. The tribute to Fellini is complete.

Radio nostalgia

But the film doesn't shy away from other references, such as to Louis de Funès, whom Cleo goes to see at the cinema with her boyfriend, or to other films that bring the family together in front of the TV set. References to the songs that set the pace in Cuarón's youth, and that punctuate Cleo's daily work. Songs that the mother listens to with her children and friends at New Year's Eve parties. Played on the radio, getting the kids up and dancing, livening up car trips. Radio. Radio. Radio nostalgia. Nostalgia for songs that made even my grandparents dance. I had the brividi - chills - when the Spanish version of one of my grandmother's favorite songs, «Il cuore è uno zingaro» - «Mi corazon es un gitano» in Spanish - appeared from the soundtrack.

A song I discovered a few summers ago, in the streets of my Sicilian village. My grandfather, at the wheel of his old green Lancia Ypsilon, my grandmother beside him, humming this song that had reappeared from their youth on a CD playing in the car: I più grandi successi della musica italiana. My sister and I in the back, carried away by the song, appropriating a youth that was not our own. Entering the nostalgia for an era we didn't live through.

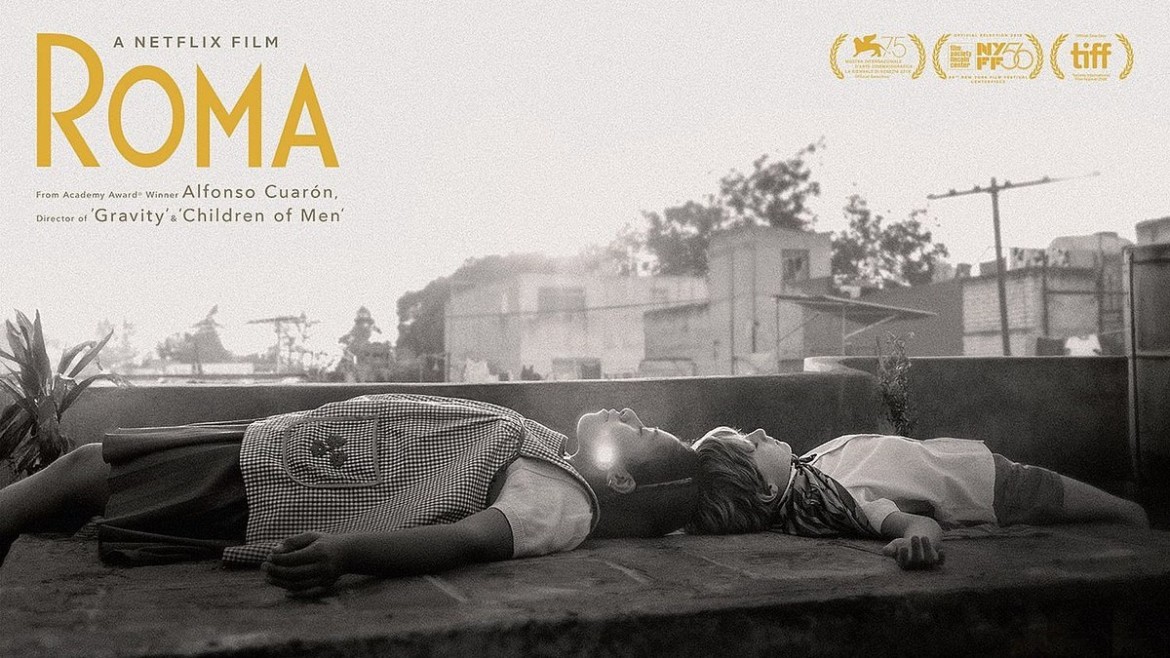

Terrace and light

I also saw again the terrace of my grandparents' house in Sicily, when Cleo hangs out the washing on the terrace of the house. The same fragrant white linen, the same freshness, the same sunshine. Roma appeals to the senses. Through the memories it evokes, through its photography. In black and white, the film produces an absolutely sublime play of light. Particularly with the sun, which without yellowing or orangeing the image, a prerogative of color cinema, floods Cleo's skin and eyes with its clarity. The terrace becomes white with sunlight. The youngest son comes to play. He and Cleo lie down under their damp clothes, embraced by the warmth of the sun, caressed by its shadow.

In addition to its sublimely beautiful light, the photograph is also impressive for the slowness of its shots. They fix rooms in the house, a burnt countryside landscape, a seascape, a plane in the sky, a car pulling up, a lifeless baby, a mother in tears, dog droppings, a tiled floor under ripples of frothy water. From the most existential tragedy to the most insignificant element, the shots touch the eye and the heart with their elegant sobriety. And since, in great films, form and substance go hand in hand, each of these shots carries a symbol that says so much about Cuarón's childhood, my childhood, your childhood, Mexico, Cleo, her condition, the condition of little people, the condition of women, life and fatality.

«No matter what anyone says, we women are always alone.»

Roots and wings

Cleo, femme fatale. Not in the usual sense. She may have a radiant face, but she doesn't have the allure of Miss Mexico. Femme fatale: a woman invested with destiny. Silent and submissive, Cleo accepts the events that befall her without wallowing in self-pity. That's what makes her nobly submissive in service, but not submissive in the face of fate. Whatever happens to her, she knows how to make a free choice. To remain a woman of integrity. To remain at the service of Sofia and her children. She chooses the love of these children, who are in a way its children. She chose to accept the fertility to which she was called, beyond the painful pregnancy she had to endure. She chooses to give tenderness, which she accepts in return from the four children who adore her. She chooses to help Sofia, accepting her help and friendship.

Cleo is always hopeful. Fatality is hard. But by accepting it, she sublimates it. She puts down roots in this family, without giving up on letting her wings spread. Roots and wings. The roots of the family's four children, whose wings are born of the love of their mother, grandmother and, of course, Cleo. The roots of Sofia, who discovers the wings of a free and strong woman in the midst of hardship. The roots of Cuarón, who gives Roma the wings of a grandiose, universal film. Fellini's roots, which made him the winged Maestro of cinema. The roots of each and every one of us, the ground from which we can soar towards full freedom, whatever our circumstances or dramas. Roma and Cleo invite us in.

Write to the author: loris.musumeci@leregardlibre.com

Photo credits: © Netflix