Turning the biography of a dictator responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths into a film is a daring gamble. All the more so when you mix dark humor and fantasy. Unfortunately, the ingredients just don't mix.

After revealing the wife of the late President Kennedy (Jackie, 2016) and inviting us into Sandringham House to follow Princess Diana (Spencer, 2021), Pablo Larraín brings us a new biopic, as fantastic as it is strange, about the dictator Augusto Pinochet. The film bridges the gap between the first half of Larraín's career, which focused on the political situation in Chile, and the second, which focused on popular political figures. Creating a film about the Chilean dictator, more populist than popular, appears to be the culmination of Pablo Larraín's approach.

A scattered promise

Augusto Pinochet (Jaime Vadell), thought to be dead, is actually living in a mansion in the middle of a desolate landscape, accompanied by his wife (Gloria Münchmeyer) and his ever-faithful butler (Alfredo Castro). The dictator looks old, and with good reason: he's over 250. He witnessed the beheading of Marie-Antoinette and vowed to fight all revolutions. He became Chile's strongman, fighting communism without mercy. But after faking his own death, the old man is tired of seeing his ungrateful people hate him. He decides to let himself wither away, but this choice quickly attracts his children, ready to tear each other apart over his legacy, and a mysterious nun who is sure to fascinate him...

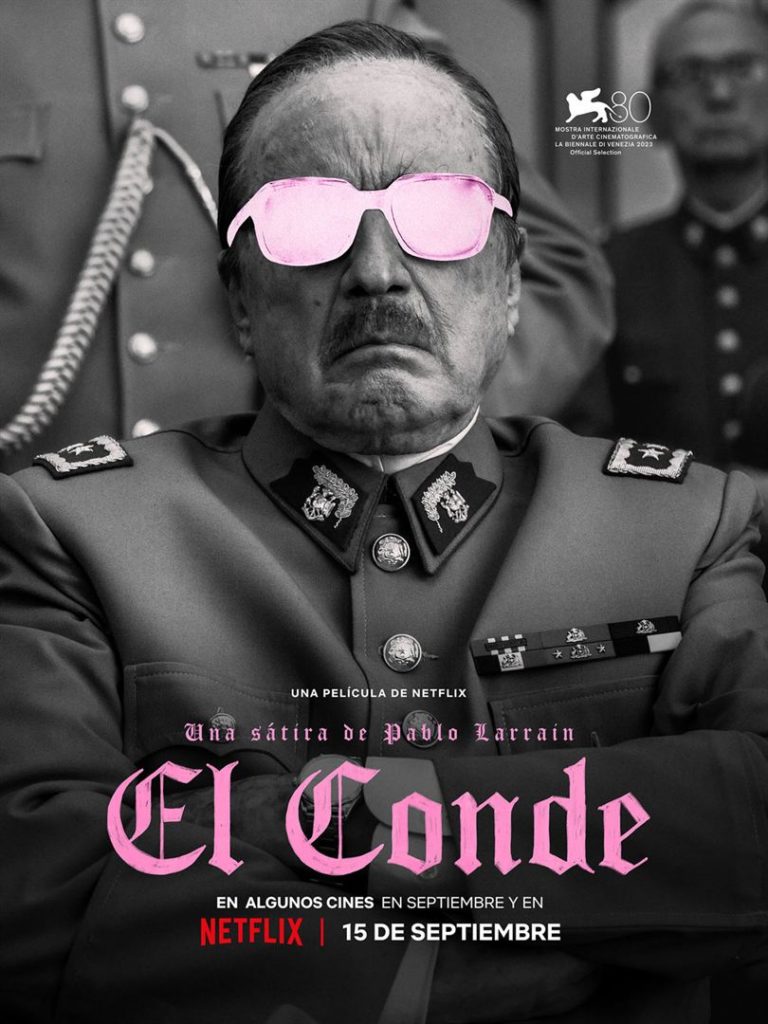

With a synopsis as intriguing as it is generous, a poster of the old dictator wearing rose-colored glasses and a few visuals of ghostly shadows soaring into the gray sky, the promotion is intriguing. It is as reminiscent of Nosferatu of 1922 in the expressionist aesthetic that a Abraham Lincoln: vampire hunter (2012) in this astonishing blend of vampirism and political biopic.

Yet all this promise struggles to bind together, and once the sense of discovery has passed, the film simply lines up ideas without really managing to shape a whole. A scene of black humor follows a contemplative surrealist scene. Then an expository scene to build the plot. Then a historical account. And we return to a brief moment of black humor. The film is less like a vampire than a Frankenstein creature. While many scenes are full of good ideas, putting them together is laborious and the grafts don't take.

The dictator's demand

By not really knowing what he wants to look like, The Count ends up lacking personality. But if there's one moment when cinema should be radical, it's when it's about a dictator. The Fall (2004), which paints an uncompromising portrait of Adolf Hitler's last days, refuses to grant man the slightest awareness of reality. King Charles V-et-trois-font-huit-et-huit-font-seize is entitled only to mockery and disgust, while the bird, the giant, the musician, the shepherdess and her chimney sweep live on Prévert's poetry (The King and the Bird, 1980). For it's worth remembering that yes, you can laugh at a dictator, as does Team America (2004), turning Kim Jong-il into a parody of the caricature that the leader had already embodied in an out-and-out comedy. It's a laugh that's frank, direct and uninhibited that the latter offers.

Now, The Count suggests irony, even cynicism. It works when we focus on the dictator's inability to understand the hatred his people have for him. But it becomes hard to laugh when the scene is followed by a stylistic exercise in which we witness the autocrat, in his cape, soar through the grayish landscape, offering a moment of surreal contemplation. These are perhaps the two scenes that work best. Alas, the film fails to connect them. The dictator is no longer a subject, but an object in the service of his author's imagination. And it's never a good idea to overshadow a dictator.

The Count sputters too often. He should have delved deeper into black comedy, like the Wadiya dictator played by Sacha Baron Cohen (The Dictator, 2012). He could also have invited us to contemplate the slow degradation of his character in his last days, as Gus Van Sant did with the mythical singer Kurt Cobain (Last Days, 2005). And if you want to witness the decline of an authoritarian political figure whose family is tearing apart the legacy, cinema hasn't yet done any better than Ran (1985), by Akira Kurosawa. The Count unfortunately proves to be an anecdotal film, lost between its artistic ambitions, its desire for black comedy and its too-often uninspired characters.

Write to the author: jordi.gabioud@leregardlibre.com

You have just read an open-access article. Debates, analyses, cultural news: subscribe to support us and get access to all our content!